Emergency events that impact animal agriculture operations can sometimes lead to the “depopulation” of entire herds or flocks of farmed animals. Depopulation involves the mass killing of animals in response to urgent circumstances. Such killings should not be confused with “euthanasia,” a term that literally means “good death.” According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Guidelines for the Depopulation of Animals, however, animal welfare during depopulations is only considered to the extent “practicable,” and minimization of pain, distress, and anxiety is far from guaranteed.

Depopulations most commonly occur in response to animal disease outbreaks, particularly those that pose a significant threat to the country’s animal agriculture industries. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, depopulation of animals occurred for a completely different reason: disruptions of the supply chain that prevented animals on farms from being moved to slaughter. The sections below highlight numerous crises during the past decade that prompted the mass killing of tens of millions of animals, in many cases using an extremely inhumane method known as “ventilation shutdown plus” (VSD+).

About Ventilation Shutdown Plus

Ventilation shutdown plus is a method of depopulation that involves trapping animals inside a building, closing off airflow, and ratcheting up the temperature (the “plus” refers to the addition of heat and sometimes steam) until the animals die from hyperthermia/heatstroke over several agonizing hours. This method likely causes extreme, prolonged suffering and does not always result in 100% mortality. For these reasons, VSD+, or any other method that relies on heatstroke as the cause of death, is not recognized as an acceptable method of killing by the World Organisation for Animal Health—the leading international authority on the health and welfare of animals.

Despite being an extremely controversial method known to cause suffering, VSD+ is classified by the AVMA as “permitted under constrained circumstances” under guidelines established in 2019, essentially clearing the way for its use in the United States. Citing the AVMA’s guidelines, the USDA has established a policy permitting the use of VSD+ as a method of depopulation—for bird flu in particular—under constrained circumstances.

The AVMA and USDA decisions to sanction VSD+, and this method’s widespread use as a result, have triggered significant pushback within the veterinary community, as the impact of fatal heatstroke on animal welfare is widely recognized within veterinary medicine. A recently published scientific paper that examines the increased use of heatstroke in mass killings of farmed animals illustrates the enormous ethical problem this poses to the US veterinary community.

Depopulation in Response to Animal Disease

Under the Animal Health Protection Act, animal disease response in the United States is overseen by the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS), in coordination with state and tribal animal health officials. The agency is authorized to order the destruction of animals in order to prevent or slow the spread of diseases that pose a threat to the economic interests of animal agriculture industries.

When it comes to diseases such as highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI)—a deadly and highly contagious strain of bird flu—the USDA’s primary control and eradication strategy to combat disease spread is “stamping out,” which refers to mass depopulation. In practice, this means that if one infection is confirmed in a flock, every single bird at that location will be killed, even if that means killing millions of potentially uninfected birds. The USDA then provides producers with indemnity payments and compensation for birds killed and eggs destroyed, as well as for the cost of cleanup.

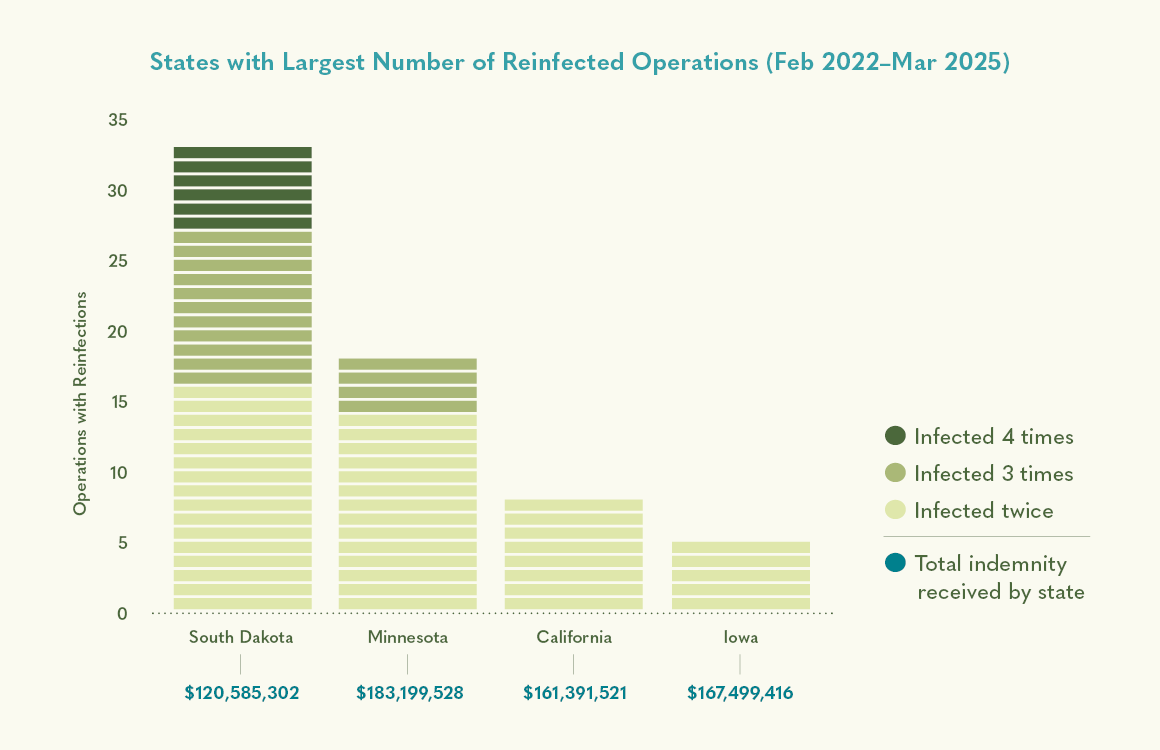

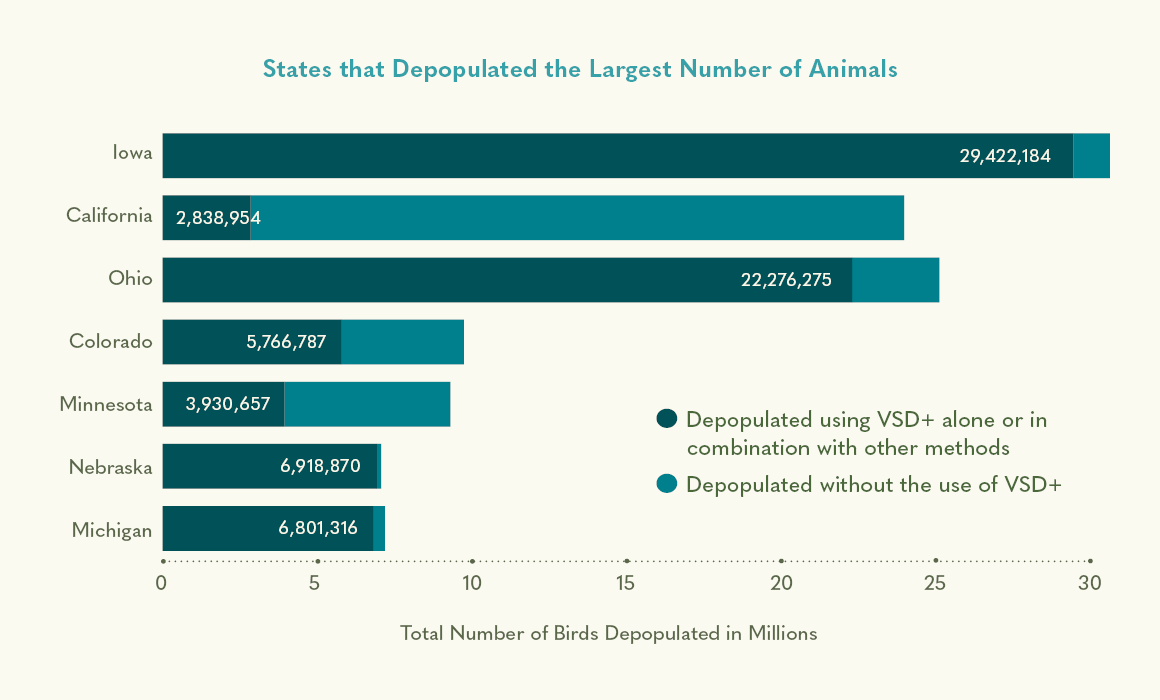

In the past decade, the United States and countries around the world have experienced two devastating outbreaks of HPAI that have impacted tens of millions of farmed birds. The first case of the most recent, ongoing outbreak was confirmed on a turkey operation in Dubois County, Indiana, on February 8, 2022. Since then, the virus has been confirmed in over 780 commercial and 900 backyard flocks across all 50 states, leading to the depopulation of over 169 million domestic birds, the majority of whom have been egg-laying hens. The current outbreak dwarfs the previous one from December 2014 to June 2015—which affected 50.4 million birds in 21 states—and has taken its place as the nation’s largest animal health emergency.

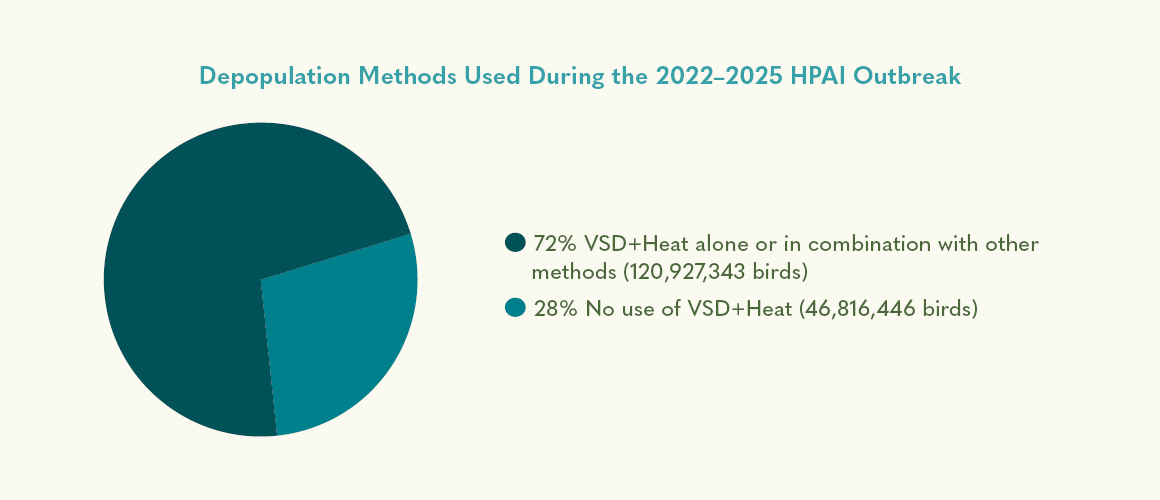

Another significant difference between the two outbreaks is the depopulation methods used. Use of VSD was not authorized by the USDA until September 2015—months after the last HPAI case was confirmed and eliminated that year. VSD (without the addition of heat) was then used for the first time on four commercial turkey operations during a brief resurgence of HPAI in early 2016. This cleared the way for future use of the method and what has transpired since. Through Freedom of Information Act requests, AWI received records from the USDA for depopulation events involving over 171 million birds impacted by the current outbreak. According to these records, approximately 123 million birds—or 72% of the birds for which data was provided—were killed in depopulations in which VSD+ was used for the entire flock or for birds in at least one barn on the premises.

Large, factory farm operations with anywhere from 100,000 to over 5 million birds are much more likely to employ VSD+, presumably due in part to the logistical challenges that arise when trying to handle and kill such a large number of animals at once—another animal welfare crises linked to the warehousing of such large numbers of animals on one operation.

Other methods used to kill birds during HPAI or other disease outbreaks include carbon dioxide gassing, which is viewed as a more humane alternative to VSD+, and water-based foam, which involves pumping firefighting-like foam into an area in which birds are contained, thereby suffocating them by blocking their windpipes; both methods cause suffering but lead to death within seconds or minutes, rather than hours. In other countries, methods that are faster and cause less suffering, such as inert gassing and high expansion nitrogen-filled foam, are used for depopulation and mass euthanasia.

Depopulation During the Covid-19 Pandemic

As was the case for many other aspects of American society, the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the livestock and poultry industries, resulting in the depopulation of hundreds of thousands of pigs and millions of birds. This occurred not because the animals were infected or posed a disease risk, but because of the high rates of human infections that disabled usual supply chains and shifted market dynamics, leaving animals in limbo within an intensive, high-production system that offers little margin for error.

In the first several months of the pandemic, dozens of slaughterhouses across the country were forced to close due to infections among workers, creating a surplus of healthy, market-weight animals on farms with no place to go. Without being able to move animals to slaughter, operations would have had to hold them longer, leading to severe overcrowding. Additionally—particularly with respect to birds raised for meat, who are bred for maximum growth in short timeframes—keeping them alive past market weight would likely exacerbate severe health problems to which they are already prone, such as skeletal and heart issues, further compromising their welfare.

In many cases, the producers’ solution was depopulation—killing all the market-weight animals on the farm and disposing of the carcasses. VSD+ involving heat and steam was used to kill hundreds of thousands of pigs. No animal should have to experience the slow, excruciating death of succumbing to heatstroke, but it was particularly concerning that VSD+ was used here—seemingly as a matter of convenience in circumstances that involved none of the urgency and uncertainty of trying to contain an animal disease outbreak.

Other methods used to kill farmed animals during the pandemic included water-based foam, sodium nitrite poisoning, carbon dioxide gassing, and captive bolt guns. In some cases, slaughterhouses used smaller crews and fewer workers to kill animals through the normal slaughter process but dispose of the carcasses rather than send them further up the (broken) chain to enter the food supply.