Humans are killing sharks at a much faster rate than sharks can repopulate. Sharks mature slowly, have slow reproductive rates, and produce few offspring—all of which makes them extremely vulnerable to extinction. Over one quarter of all known shark species are considered threatened or endangered. Sharks are apex predators in many ecosystems, and their disappearance is causing dangerous imbalances in marine communities worldwide. Without sharks, the health and productivity of our oceans—and dependent livelihoods and economies—are at risk.

Many shark populations have faced steep declines due to years of exploitation for their fins, cartilage, meat, and liver oil. There is a robust global market for shark fins in particular to meet the demand for shark fin soup. Shark fin soup is a popular (and pricey) dish in some East Asian societies, prized as a symbol of prosperity. It is traditionally served at banquets and on special occasions such as weddings. Continued demand for shark fin soup, dumplings, and other shark fin dishes served in restaurants around the world perpetuates the practice of finning, resulting in an estimated 73 million sharks being killed each year for their fins alone.

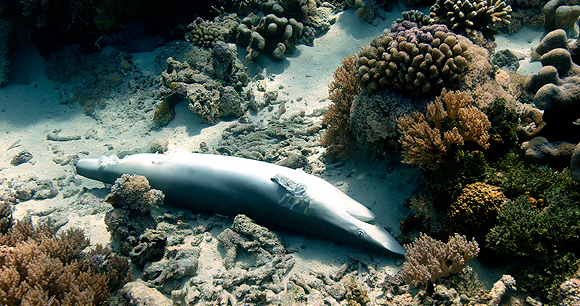

Because of the high commercial value of shark fins and the relatively low value of shark meat, fishers often take only the fins and leave the rest of the body behind—an extremely cruel and wasteful practice. Typically, sharks are finned alive—brought aboard fishing vessels to have their fins sliced off, then thrown back into the sea, where they suffocate, bleed to death, or are eaten by other animals. Appallingly, the animals are usually conscious through much of the ordeal.

Approximately 50 million more sharks die annually as bycatch in unregulated fisheries, often through the use of destructive and indiscriminate fishing methods such as longlines, gillnets, and trawls. The international shark fin trade is largely unregulated, so sharks caught accidentally are routinely killed for their fins.

Although over 100 shark species appear on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, less than half receive global protection through trade restrictions. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) regulates international trade in species to ensure their survival. Those shark and ray species that are listed in the CITES appendices are mainly listed on Appendix II (for species that may become threatened with extinction unless trade is closely controlled). The only exceptions are all seven sawfish species, which in 2007 were added to Appendix I (for species considered endangered and for which most trade is prohibited).

At the 19th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to CITES (CoP19) in 2022, the parties agreed to regulate trade in more than 50 species of requiem sharks threatened by the demand for shark fin soup, including blue, tiger, and bull sharks, as well as several species of hammerhead sharks and 37 species of guitarfish. At CoP18 in August 2019, 18 species of sharks and rays—including shortfin and longfin mako sharks, six species of guitarfish, and 10 species of wedgefish—were added to Appendix II, thus gaining some trade protections. Appendix II trade protections have previously been achieved for a number of shark and ray species, including basking and whale sharks in 2003; great white sharks in 2005; oceanic whitetip, smooth hammerhead, scalloped hammerhead, great hammerhead, and porbeagle sharks, plus all species of manta rays, in 2014; and thresher and silky sharks and all species of mobula rays in 2017.

AWI has long asserted that sharks need stronger protection from the cruelty of shark finning. Given the fragility of shark populations, we have led efforts to compel restaurants in US states and territories that are known for serving shark fin soup, dumplings, and other shark fin products to cease doing so. Read more about international efforts to protect sharks and AWI's shark fin campaign, including a list of restaurants to avoid in the United States and Canada that offer shark fin soup.

A long-awaited victory occurred in December 2022 when the Shark Fin Sales Elimination Act passed the US House of Representatives as part of the National Defense Authorization Act (HR 7776). President Biden signed the bill into law before the 117th Congress adjourned, prohibiting the sale, purchase, possession, and transport of shark fins or products containing shark fins. The federal ban is a significant win for animal welfare and marine ecosystems worldwide, which we hope will set an example for other nations.