by Alexander Greig

The common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) is increasingly becoming a key species in behavioral and biomedical research. Because of this, research focused on improving the behavioral and physiological welfare of this species is critical to housing this species in laboratories successfully. Agonistic behaviors between groups of common marmosets are well documented in both field and laboratory conditions. Interactions between groups of wild common marmosets often result in contact aggression. Captive marmosets display increased agonistic intergroup behaviors such as anogenital displays and piloerection during periods of higher levels of vocalizations from neighboring groups.

Numerous studies have documented how the social environment that marmosets are exposed to can affect glucocorticoid responses to external stimuli. This led us to hypothesize that limiting visual access to neighboring pairs would decrease social agonistic behaviors, leading to increased behavioral indicators of positive welfare and decreased glucocorticoid levels.

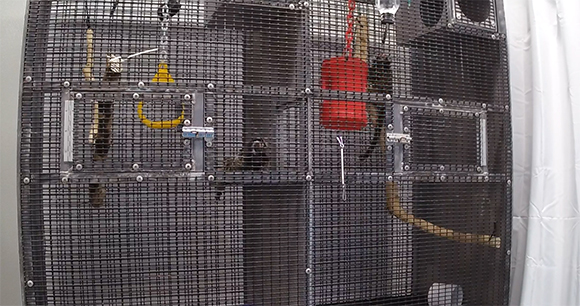

This study, which was supported by an AWI Refinement Research Award, was conducted at the Southwest National Primate Research Center on eight breeding pairs of common marmosets between 2 and 7 years of age. The animals were exposed to three conditions in an ABA-style experiment (i.e., comparing baseline, treatment, and return to baseline within each group), with each phase lasting three weeks. The animals were completely removed from visual contact with neighboring groups for three weeks during the treatment phase, using either folding room partitions or white polyester curtains suspended from tension rods (see above).

Behavioral observations were conducted using video data in 10-minute sessions chosen randomly between the morning and afternoons for the first two weeks of each phase of the experiment. Proximity, social behaviors, and scent marking were recorded using the ZooMonitor app (Lincoln Park Zoo, 2020). Locomotion was scored by hand using instantaneous focal sampling with 15-second intervals, alternating between individuals for each session. The first defecation of the day was collected every weekday for three weeks in each condition.

We discovered that when the visual barriers were in place, animals spent more time allogrooming (p=0.004), less time apart (p< 0.006), and less time in locomotion (p<0.001). They also had fewer occurrences of scent marking (p=0.031). However, fecal cortisol levels were elevated (p<0.001) during this time, compared to both baseline and post-experimental levels.

These results indicate that restricting visual access between neighboring pairs of marmosets improves multiple behavioral indices of positive welfare, as hypothesized. Paradoxically, restricting visual access was associated with increased levels of cortisol. One explanation may be that while social stressors were removed, resulting in increased behavioral indicators of positive welfare, the introduction of the curtains may have been an environmental stressor, leading to increased cortisol concentrations. This may indicate that while removing social stressors is important, stability in the home environment is equally, if not more, consequential physiologically. A follow-up study in which marmosets are gradually habituated to the curtains or partitions may help confirm whether visual barriers improve the overall welfare of captive marmosets.

Alexander Greig is a behaviorist at the Southwest National Primate Research Center at Texas Biomedical Research Institute