JAS B. BARLEY, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK

LORRAINE BELL, University of Colorado-Health Science, Denver, USA

RICHARD DUFF, Loyola University, Maywood, USA

AMY KERWIN, University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA

KATHLEEN CONLEE, Humane Society of the United States, Washington, USA

CATHY LISS-SWETLOW, Animal Welfare Institute, Washington, USA

VIKTOR REINHARDT (Moderator), Animal Welfare Institute, Washington, USA

Address for correspondence: Viktor Reinhardt, 6014 Palmer Drive, Weed, CA 96094, USA; E-mail: [email protected]

"At our facility, we have recently started working with a new vendor who is regularly selling us pound dogs as opposed to our old vendor who sold us primarily hounds and purpose-bred dogs. It is a lot more difficult for me to work with pound dogs, such as a golden retriever or a labrador than with the hounds since I know they were indeed companion animals at some point. These animals still exhibit many signs of companion animals, such as knowing how to sit and give paw, wanting to play fetch with a toy, or just seeking human attention and affection. I feel I can offer these companion animals who have abruptly been turned into research animals some comfort, knowing what they were probably accustomed to a home environment and trying to re-create that as much as I can while they are here. Because of my experience as a dog owner, it's easier for me to provide enrichment to ex-companion dogs from pounds than to hounds and purpose-bred dogs who are more aloof, although some do play" (Anonymous).

"I would think that a dog moving from a loving home to a pound, and then to a research facility would (1) act differently from a dog who has been purposely bred and raised for research, and (2) be distressed and, therefore, immunocompromised. Both circumstances are likely to confound physiological and behavioral research data collected from such an animal" (Kerwin).

"Having seen how some people keep their pets and the cruelty inflicted through, at best ignorance but often indifference, I don't think it's safe to assume that animals at home are always having a good time. In fact, in a lot of cases they would probably be better off in the lab at least as far as regular food, cleanliness and caring goes. Although it's been illegal in the UK since 1906 to supply stray or 'Pound' dogs for research, I remember the time when we worked with dogs and cats who were ex-pets. It was emotionally very disturbing and all the techs and the majority of the researchers I worked with found this circumstance extremely difficult to tolerate, even though we knew that the owners had willingly surrendered/sold their pets to our supplier. We were lucky in that the researchers used to turn a 'blind' eye to our re-homing schemes and entered into the records that the animals for whom we found a new home had died from 'natural' causes. Since the advent of the Animals [Scientific Procedures] Act 1986 all dogs and cats must originate from registered breeders, except in circumstances where a project license authorizes research which is breed-specific. Over the last few years we have been working with varying degrees of success on re-homing programs for our ex-research dogs" (Barley).

"Since our facility has a fairly strong adoption program, I'd much rather we use pound animals as that gives these dogs a chance to be adopted into a good home. In addition most pounds in the US can only hold animals for about 5-7 days before they are euthanized. At my prior facility we actually removed dogs from the pound's euthanasia area just prior to their being killed (literally minutes before). In the two years that I worked there we were able to return four dogs to their owners. While that's not a big number, you have no idea how good it felt to be able to bring these animals back to their original homes. Obtaining stray animals from pounds right before they are scheduled to be euthanized for research rather than purpose bred or Class B dealer animals would probably help reduce the total number of animals who have to be euthanized each year simply because no adoption home can be found for them in time" (Bell).

"That's a really good point about pound dogs. By using some of them, we are making space for animals that may get a second chance at life through adoption. But I must admit, it is generally more difficult to work with a dog from the pound because he/she has more `pet' qualities than a purpose bred or hound dog. You often can get quite attached to such ex-companion animals. I wish we could adopt some more of our dogs out. It is greatly frowned upon here and, so far, we have only managed to adopt out one dog. We, as animal technicians would like to be able to do it more frequently but our management is not very supportive. Obviously, in some instances adoption is not an option, but we do have some protocols in which adoption would be feasible" (Anonymous).

"At our facility we have an adoption program and have successfully placed quite a few animals. If research laboratories could purchase pound animals who are scheduled to be euthanized because no new home could be found for them in time, the pound would make enough money to allow for a longer stay of ex-companions animals, thereby increasing their chances to get finally adopted. I'd much rather see dogs or cats used for research purposes than killed in pounds. The hard part is convincing the `general public' that those animals to be used for research would be sold just prior to euthanasia and not at the whim of the people running the pound, and guaranteeing that the pound's personnel didn't profit from the disposition of the animals" (Duff).

"In regards to use of `pound' animals for biomedical research, you have to consider the other side of the issue, the effectiveness of the shelter itself. Let me share sections of the position of the Humane Society of the United States. The HSUS `is convinced that the surrender of impounded animals from public and private shelters to biomedical research laboratories, training institutions, pharmaceutical houses, and other facilities that use animals for experimental teaching or testing purposes contributes to a breakdown of effective animal-control programs through abandonment of animals by owners who rightfully fear such animals may be subjected to painful use. The Society believes that animal shelters should not be a cheap source of supply for laboratories. .. It is, therefore, the policy of the HSUS to oppose the release of impounded animals from public and private animal shelters to biomedical research laboratories. .. Further, the Society condemns any organization, calling itself a humane society or a society for the prevention of cruelty to animals, that voluntarily sells or gives animals in its custody to biomedical research laboratories" (Conlee).

The position of the Animal Welfare Institute on the use of pound animals is less uncompromising. "`The great majority of experimental animals are bred for the purpose. This is the preferred method of acquiring animals. .. Dogs and cats, for use in experiments under full anesthesia from which they are not allowed to recover but pass directly into death, may be obtained from among animals already condemned to death in pounds because no homes can be found for them. This simply constitutes a change in the place where euthanasia is conducted.' Our policy aside, if animals from pounds are supplied to laboratories, the owners should be informed and provide their consent. Stray animals (whose owners clearly cannot give their consent) should not be provided to laboratories. Often people have difficulty locating their missing/stray companion dog or cat. It behooves research staff to be able to assure the public that no `owned' dog or cat is on their premises.

Class B random source dealers should never be used as a source for dogs and cats. Random source dealers are adept at flouting the Animal Welfare Act. They can purchase animals from individuals who claim to have bred and raised the animals as mandated by law, even though this may not be true and the animals were stolen, acquired by fraud or were simply not bred by the supplier. In the rare instance that United States Department of Agriculture [USDA] investigates, the dealer can claim ignorance and, since the person selling the animals to the dealer is not licensed by the department, USDA will not take action against him/her. I visited a research laboratory that purchased dogs from various Class B dealers. This facility maintained a bulletin board to post information about missing companion animals. When people from the local community called to notify the facility about missing dogs and cats, reports were dutifully hung on the board. Each caller was relieved to know that the facility was `acting responsibly.' The problem with this scenario is that missing pets never turned up at the facility simply because it was located in a northern state and obtained its animals from Class B dealers who get their dogs and cats from a number of different states in the midwest. The moral of this story is that if dogs and cats are acquired from sources other than Class A breeders, every effort must be made to insure that each animal is supplied legally and that beloved companion animals don't mistakenly end up in a research lab. It should be emphasized here again that random source dealers are legally entitled to acquire animals from pounds and to sell these animals to research institutions. I think, it would be much better if research facilities could deal directly with the pound rather than involve a middleman who may subject the animals to additional suffering" (Liss-Swetlow).

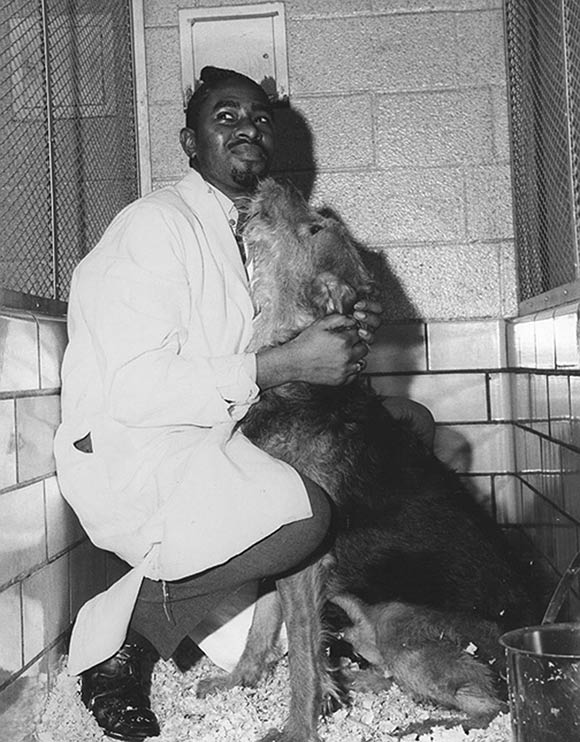

"To summarize, working with pound dogs is emotionally more challenging but at the same time often more rewarding than working with purpose-bred dogs. The affectionate human attachment is a warranty for the pound dog to receiving optimal care and being treated with as much consideration as possible (Figure 1). Research laboratories should accept a dog from a pound only under the condition that it is documented that the animal is already scheduled to be euthanized because re-homing attempts were unsuccessful. Adoption programs are highly valued by animal technicians as these avoid the often unnecessary killing of ex-research dogs. Such programs should be developed, followed and supported by each research facility" (Reinhardt).

Reproduced with permission of the Institute of Animal Technology.

Published in Animal Technology and Welfare 3(3), 165-167 (2004).